(Warning: level of aikido jargon: moderate)

Training with kids - and especially teaching them - is an exercise in maintaining the balance between discipline, caring and expelling energy.

Training with kids - and especially teaching them - is an exercise in maintaining the balance between discipline, caring and expelling energy.

I was a scout leader for many years before I moved to the UK, so I have some experience of children aged 6-7 and above. Nevertheless, I find the capacity of children to pick up aikido amazing. As I mentioned in the previous post, some children start understanding aikido, instead of just imitating it, at 8 years old - some might be even younger.

|

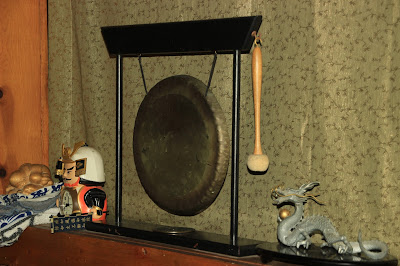

| When the gong rings, the children sit down to wait for class to start. Theoretically. |

Class starts with a warm up, during which we count in Japanese (probably teaching me more than the children). The class itself takes the same format as the adults’ class, which I described in the previous post. At the end of a class we do Japanese: each child can ask sensei for a word in Japanese. We’ve heard everything from ‘sun’ to ‘sequin’, ‘chrysanthemum’, ‘insight’ and ‘Stegosaurus’. Sometimes a child will say a Japanese word - like O’Sensei or ninja - and then sensei does a reverse translation. She might also give a short explanation of something to do with Japanese culture that relates to the word - for example, ninjas used as a password the three strokes that together make up the kanji for ‘woman’ - the first ninjas were female. If there is time at the end, we play dodo, a very confusing game of tag.

It is tough to teach children of all levels and of all ages in the same class. There are a lot of things that children don’t really get taught, but they just pick up along the way, like ukemi (rolls). Sensei will show 2-4 different techniques, so that lower ranks do an easier technique while higher ranks do a more complicated one. (Sensei also applies this to adults, but usually only with 2 different techniques.) After a few weeks I’ve more or less got my head around which rank does which techniques, but sometimes if I’ve been distracted I try to cover it up with sneaky tactics: I look around to see what everybody else is doing. If I get distracted by a restless child, I can’t really scold the children for the same.

Unless it is a bad day, it is possible to train your own aikido, rather than just babysit. Kids’ class is especially good for learning to bend those knees and drop those hips. Extensions are easier to achieve but have to be more precise and controlled. Sometimes shihonages and uchi kaiten sankyos (techniques where I have to pass under my attacker’s arm) transform into hanmihandachiwaza (meaning that I drop down onto my knees). And, of course, there is randori.

Randori (free practice, often against multiple attackers) with children is so much fun. Just watching them is great. Randori is part of every class and around their birthdays the children get an extra randori, a birthday randori. The children just love it. During randori those who have been restless or slow to do the techniques during class transform into budokas. Their concentration is obvious. Their enjoyment is obvious. And their skill is astounding. Some of them are better at it than adults. A three-year-old can take on two ukes (attackers). Red belts, who might be 10 years old, will take on four ukes. But then again, they might have been doing aikido for 7 years already.

Not every class is great, of course. On one rainy day, all of them were fidgety. Getting them to sit in line before class was a mission impossible. When class started, their concentration was elsewhere. One child I trained with wanted me to spell her name (“This is a class in aikido, not in spelling”). Another one was so slow to bow to me, get up and grab my wrist that I barely had time to do the technique before we moved onto the next one. One would slowly crawl - rather than knee walk - back to line. But when we got to randori, all that was gone.

After class the children sweep the mat. Some of the older children try to get the younger ones to move together from one end of the mat to the other, instead of running down the mat with the broom behind them. Wielding the dustpan and brush is a position of honour.

After that is ‘go and catch Noah’ or ‘go and catch one of the bigger kids’ time.

The real sweeping gets done after the adults’ class.